BACKGROUND

Delirium is a complex and often under-recognised condition with potentially profound consequences for hospitalised patients.1,2 Defined as an acute and fluctuating disturbance in attention and cognition, delirium is a common phenomenon with several risk factors among patients, negatively impacting morbidity and mortality.3 While delirium is prevalent in wards and units, its management remains a complex endeavour.4–8

Implementation of delirium management strategies in critical care is a multifaceted process impeded by many different factors,9 such as the often complex aetiology of delirium, under-recognition of the condition, reduced staffing, polypharmacy and procedures, and else.10,11 Facilitating factors, on the other hand, are the implementation of guidelines and protocols, the pursuit of a multi-professional and multidisciplinary management approach, non-pharmacological prevention and treatment measures, family- and patient-centred care and education.12–15 Recognising and acknowledging these challenges and facilitators can lead to more effective delirium management.16 Frequent service evaluations are used to assess the quality of care and identify improvement areas. In our hospital, delirium awareness appeared low; delirium was recognised as frequent but harmless. Other challenges were high workload due to nursing shortage, missing opportunities to document delirium, routine care prioritisation, lack of delirium management protocols, consequences of positive assessments, missing knowledge, and reduced interprofessional communication. These problems are common and well-known in the literature.17–20

Interprofessional education (IPE) is defined as learning of members or students of two or more professions with, from, and about each other to improve collaboration, quality of care, and service.21

IPE in hospital settings plays a pivotal role in improving patient care and delirium outcomes and promoting collaboration.22 It is designed to equip healthcare professionals from various disciplines with the skills, knowledge, and attitudes necessary to work together effectively as a team.23–25 The German Interdisciplinary Society of Intensive Care Medicine (DIVI) recently developed a curriculum for an IPE course about delirium management, aiming to deepen and extend delirium-specific knowledge and enable clinicians to improve their treatment strategies.26 The delirium curriculum is available in German language: https://akademie.divi.de/images/Dokumente/DIVI Curriculum-2023-11-26.pdf

We aimed to assess whether an IPE course for delirium management would empower clinicians to conduct quality-improvement projects involving interprofessional and interdisciplinary approaches in their hospital.

METHODS

We report this quality improvement (QI) project following the Revised Standards for Quality Improvement Reporting Excellence (SQUIRE, supplementary material)27 and Good Clinical Practice.

Context

Sana Kliniken Niederlausitz is a university-affiliated hospital in Germany, providing specialist care, 543 beds, and 1,200 employees. Before starting the project, no delirium management protocols or other pertinent service assessments existed.

Intervention

The DIVI-certified IPE course for delirium management contains 20 teaching units, each 45 minutes long, on delirium with a focus on intensive care and emergency medicine.26 It delivers essential knowledge on delirium, educates on delirium management strategies, and provides implementation recommendations based on a plan-do-check-act (PDCA) cycle. The curriculum is designed for interprofessional and interdisciplinary stakeholders. Providers decide on the exact educational approach, including case-based (e.g. case study discussions), reflective (e.g. discussing experiences and ideas from different perspectives), simulated (e.g. role plays) and problem-based (e.g. design and launch quality improvement projects) learning. The program is completed in two full working days with breaks and includes a four-hour evaluation meeting eight weeks later.

Implementation of delirium management is a complex process. Aspects such as the intervention itself, but also organisational culture (structures, processes, readiness and ability to change), local conditions (staff, laws, regulations), and clinicians (attitude, knowledge, competencies), including related barriers and facilitators need consideration.28

Measures

At the end of the first two days, participants organised themselves into different groups and reflected on possibilities for optimising delirium management on their wards and units, identifying and assessing both barriers and facilitators. They then gave a short report and defined a feasible eight-weeks goal.

Analysis

We evaluated participant ability to perform self-defined QI projects in their wards and units. Primary outcome was the number of successful projects at the eight-week evaluation meeting.

Ethical Considerations

Due to the character of a service evaluation and improvement, no ethics approval was required.

RESULTS

The IPE course for delirium management took place in August 2023, with follow-up evaluation on 03/10/23. Participants were 50% (n=8) registered nurses, 37.5% (n=6) therapists, and 12.5% (n=2) physicians of various disciplines from the emergency department, intensive care unit, geriatric acute ward, neurological ward and stroke unit, and interdisciplinary physiotherapy and occupational therapy.

Development of the projects

Participants had several opportunities to interact and were motivated to change practice. They appreciated the interprofessional and interdisciplinary discussions and shared their perspectives and ideas. Finally, participants organised themselves into five groups. First, barriers were reflected, such as staff shortage or missing opportunities for documentation (organisational barriers), time pressure and low frequency of delirium assessment (local barriers), lack of knowledge about delirium or complaining attitude (clinicians’ barriers), and others (Table 1). Due to nurses, physicians, and therapists’ different views on the barriers, participants developed solutions for specific questions. Finally, they developed feasible ideas for SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timely) projects.

Details of the process measures and outcome

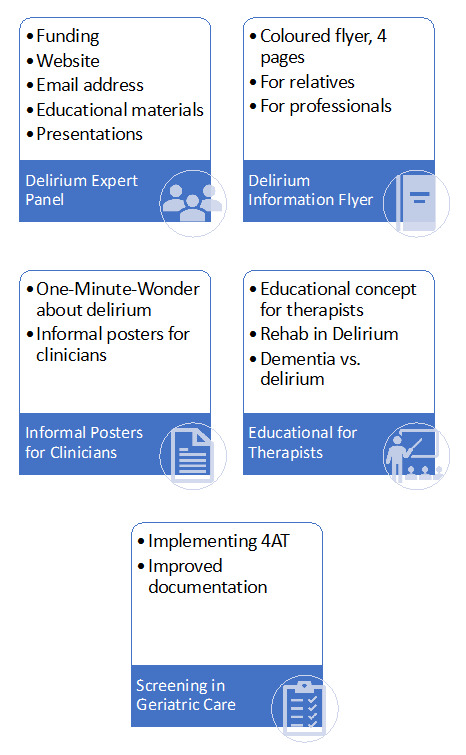

Participants organised themselves into five different project groups:

-

Project Delirium Expert Panel

This project aimed to establish a plan for an interprofessional leading group of delirium experts within the hospital. At the timepoint of the second meeting, the group presented a full project plan for the coming year. The plan includes a dedicated presence on the web and distributing information about delirium to other clinicians in the hospital. Further aims are recruiting more clinicians, organising team training, and developing teaching materials for staff and family caregivers. -

Project Delirium Flyer

The goal was to design and print a flyer for relatives of delirious patients on intensive care units. This group presented a first sketch of a folded, full-coloured flyer, including delirium information and what relatives can expect and do. Design elements were very well considered. During the discussion of the sketch, the focus was extended from critical care to the whole hospital. -

Project Team Education

The goal was to educate all the multidisciplinary and multiprofessional teams. Hence, the group developed a one-page summary sheet, which could be printed as a flyer, hung up on walls, and referred to further information from the delirium experts. -

Project Training for Therapists

The goal was to develop a training session for therapists. In this hospital, therapists are organised centrally. Hence, this specific training includes general knowledge about delirium in different populations across the hospital, the differences between delirium and dementia, assessments by therapists using the 4AT screening tool, and therapeutic interventions with a focus on safety and caring. -

Project 4AT Assessment in Geriatric Acute Ward

The goal was to implement a frequent assessment of delirium using the 4AT. The group communicated with IT to initiate an update to the electronic patient charts. This process is time-consuming but potentially supports hospital-wide implementation. Until completion, the group considered additional paper sheets for documentation of delirium assessment. The group could not meet their goal within the defined timeframe of eight weeks; the project is ongoing.

Contextual elements that interacted with the intervention(s)

During the concluding discussion on the third day, participants appraised the IPE course positively. They reported an improved knowledge and attitude towards delirium management. Participants were satisfied with the structure, process, content, and methods. They reported feeling more confident in providing care to patients with delirium and performing quality improvement projects in their hospital. Participants felt additional improvement in learning could be achieved through training in a simulation centre or with actors portraying delirious patients.

Observed associations between outcomes, interventions, and relevant contextual elements

Most clinicians generally provided basic delirium prevention measures, such as vision- and hearing aids, calendar, or clock. But in the initial phase, delirium awareness and management were still variably implemented. There were differences within the departments and professional groups. Delirium screening was carried out irregularly on normal wards but regularly thrice daily on intensive care units. In the emergency room, the priority was on treatment of severe hyperactive delirium. On general wards, delirium superimposed on dementia was seen as a central challenge, and in intensive care units, appropriate pharmacological treatment was a core question. Consequences of positive assessments were different within departments and professions and might be related to interprofessional communication. While different needs required different solutions, participants benefitted from each other’s discussions and solutions. After the initial two days of IPE, they had increased awareness regarding delirium, tested the screening in their daily routine, searched for interprofessional communication, and acted as multipliers in their teams.

Further observations

After the first training days, participants were asked for their experiences by their colleagues, and participants could use this interest to inform them about delirium, to raise their delirium awareness.

Participants also reported difficulties managing the differences between expectations and practice, e.g., correct delirium assessment, communication with other professions, missing structures, etc.

Details about missing data

The interactive nature of the project prevented the collection of missing information related to interesting aspects.

DISCUSSION

In this quality improvement project, a two-day DIVI-certified IPE course for delirium management enabled participants to assess local barriers and to develop improvement projects for the hospital and/or their wards/units. Eight weeks after attending the IPE course, four of five groups of clinicians presented projects with successful and continuing implementation, such as establishing a hospital’s delirium expert panel, delirium flyers for family caregivers, an information one-pager for healthcare professionals, and a teaching concept for training therapists; only implementation of 4AT in electronic patient charts was ongoing. Additionally, the clinicians reported being satisfied with the course and felt more competent to care for delirious patients.

The IPE course for delirium management addresses interdisciplinary and interprofessional hospital staff. Training on delirium management is fundamental for patient care and can be made successful through repetitive training.24 It is equally important that the training is sustainable and reflects current knowledge.29,30 According to the IPE course, the DIVI-certified delirium expert receives training on current specialist knowledge and support for developing a delirium-oriented attitude through interprofessional communication and collaboration. Another notable feature of this class was that the participants developed and implemented projects according to the PDCA cycle after training in small groups (4 out of 5 successful). By working successfully in small groups over eight weeks, the step from acquiring specialist knowledge through the IPE course to implementation was completed. As other groups proved, this could be a more successful path than ‘just’ repetitive training.22

The implementation of the first projects was facilitated by the PDCA cycle accompanying the training. An appropriate time frame and active participation of the involved staff members are critical for success.23 Identifying and discussing barriers within local context is essential for finding possible and practicable solutions. One barrier was a need for additional training and structural improvements in the hospital.22 Other barriers such as interprofessional and interdisciplinary collaboration, can be strengthened, e.g., by shared daily rounds, implementing quality indicators, daily rounds, and documentation of daily goals.31,32 It is essential to assess not only satisfaction with the course but also the sustainability of strategies and the well-being of healthcare professionals.30 In this context, specific areas such as stroke and neurological units require a distinct approach.33 Follow-up audits are still pending implementation.23 After implementation, routine monitoring and reassessing the conditions are necessary for ongoing improvement.30

At this stage, cost evaluations could not be performed.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of this work are: a) a structured, interactive QI project with clinicians from several wards/units across the hospital, using intrinsic motivation and expert knowledge across different disciplines and professions; b) the documentation of this project, enabling transparent reporting of each step; c) motivated hospital management who appreciated the funding and development of their delirium-specific QI group.

Limits to the generalisability of the work include: a) IPE-related limitations such as methods and measures, amount of interaction and time schedule, presentations, or personality which might have hampered individual learning progress in participants; nevertheless, participants’ feedback was most positive, and the limitation might be less relevant; b) the setting, culture and specific team-communication of a university-affiliated hospital in East Germany; results might be different in other settings and cultures; c) most reported projects included planning of projects only; nevertheless, we believe that establishing structures and processes is a fundamental step in hospital-wide projects and represent a project by itself; d) long-term sustainability of these projects have not been proven; hence, this success on patients, staff, economics, or even society cannot be reported, yet; contrary, the overall project just started and will be followed by the research team.

CONCLUSIONS

The IPE course for delirium management motivated and enabled participating clinicians to develop and perform delirium-specific projects in their hospital. Further research is needed to evaluate the sustainability of these projects and to estimate the effect of influencing factors within the context of the culture and setting. The next steps will be establishing delirium management, disseminating knowledge, improving care quality, and evaluating the benefits.

Acknowledgement

We are thankful for all participating healthcare professionals who helped us to perform this quality improvement project.

Contributions

All authors FS, VH, UG, HCH, TD, RvH, CH, CHo, AK, SP, and PN made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; FS, VH, and PN have drafted the work; UG, HCH, TD, RvH, CH, CHo, AK, and SP substantively revised it; all authors FS, VH, UG, HCH, TD, RvH, CH, CHo, AK, SP, and PN approved the submitted version (and any substantially modified version that involves the author’s contribution to the study); all authors FS, VH, UG, HCH, TD, RvH, CH, CHo, AK, SP, and PN agreed to be personally accountable the accuracy and integrity of any part of the work.

Ethic approval and registration

The quality improvement project was performed in concordance with the declaration of Helsinki and Good Clinical Practice. Due to the character of a service evaluation and improvement, no ethic approval was required.

Funding

This work is not funded.

Declaration of Interests

The authors report no conflicts related to this work.